In what many economists are calling a paradox of modern finance, bond investors continue to demonstrate remarkable appetite for government debt even as fiscal metrics flash increasingly urgent warning signals. From Washington to Brussels, Tokyo to London, sovereign debt levels are reaching historic peacetime highs, yet bond markets appear to be operating under the assumption that fiscal discipline remains a distant, theoretical concern rather than an immediate economic imperative.

The phenomenon has left seasoned analysts scratching their heads. Traditional economic theory suggests that mounting government debt should trigger higher borrowing costs as investors demand greater compensation for increased risk. Instead, we’re witnessing the opposite: yields remain historically low, spreads are tight, and demand for government paper continues to outstrip supply in many major economies.

This disconnect between fiscal reality and market pricing represents one of the most significant puzzles in contemporary finance, with implications that extend far beyond trading floors and into the realm of monetary policy, political governance, and long-term economic stability.

The Numbers Behind the Paradox

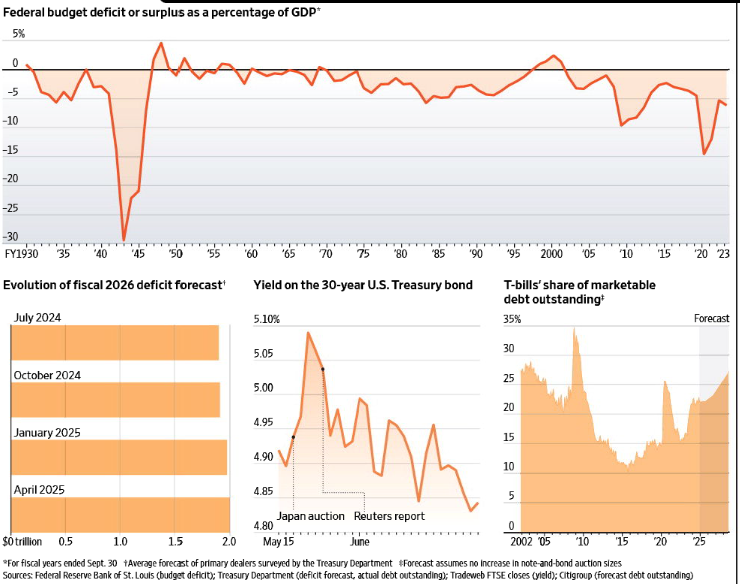

The scale of global fiscal expansion over the past several years has been unprecedented in peacetime. The United States federal budget deficit, which reached historic lows near zero in the late 1990s, has swung dramatically into negative territory. Recent data shows the deficit spiking to nearly 15% of GDP during crisis periods, with current projections suggesting it will remain elevated at approximately 7-8% of GDP through 2025 – levels that would have triggered market panic in previous decades.

The trajectory is particularly striking when viewed in historical context. From the relative fiscal discipline of the 1990s and early 2000s, when deficits typically ranged between 2-4% of GDP, the current era represents a fundamental shift in fiscal policy tolerance. Even as the deficit is forecast to improve slightly from recent crisis peaks, it remains at levels that economists traditionally associated with wartime spending or severe economic emergencies.

Japan, long considered the canary in the coal mine for sovereign debt sustainability, has pushed its debt-to-GDP ratio past 250%, yet continues to issue bonds at yields that would have been considered impossible just two decades ago. Even emerging market economies, traditionally held to stricter fiscal standards by international investors, have found receptive audiences for their debt issuances despite deteriorating fundamentals.

The International Monetary Fund’s latest Fiscal Monitor paints a sobering picture: global government debt is projected to exceed $100 trillion by year-end, representing approximately 100% of global GDP. Primary deficits – the gap between government spending and revenue excluding interest payments – remain stubbornly high across major economies, suggesting that the debt accumulation is structural rather than cyclical.

Perhaps most concerning is the trajectory of interest expense as a share of government budgets. In the United States, net interest payments are projected to consume an increasingly large portion of federal revenues, crowding out spending on infrastructure, education, and other productivity-enhancing investments. Similar dynamics are playing out across the developed world, creating what some economists describe as a “fiscal doom loop” where debt service costs consume an ever-larger share of economic output.

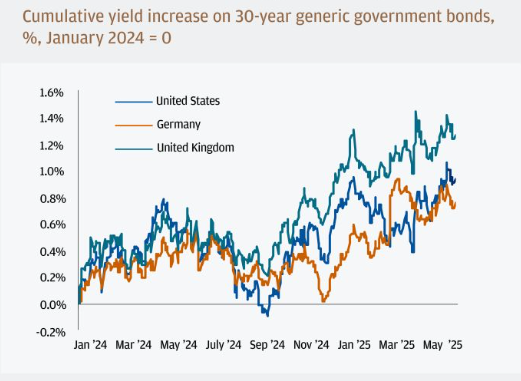

Yet despite these alarming fundamentals, bond markets continue to price sovereign debt as though fiscal sustainability remains intact. The yield on the 30-year U.S. Treasury bond, which peaked above 5.10% in late 2024, has since moderated to around 4.85% – a level that many analysts argue fails to adequately compensate investors for the long-term fiscal risks embedded in current policy trajectories.

Central Bank Intervention: The Invisible Hand

One of the primary explanations for this apparent market complacency lies in the unprecedented role that central banks have assumed in government bond markets. The era of quantitative easing, which began as an emergency response to the 2008 financial crisis, has evolved into something approaching a permanent feature of monetary policy architecture.

Central bank balance sheets have expanded to accommodate massive holdings of government securities, effectively removing significant portions of sovereign debt from private market determination. When the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and other major central banks collectively hold trillions of dollars worth of government bonds, the traditional price discovery mechanism becomes distorted.

This central bank presence creates what economists call a “put option” under government bond markets – an implicit guarantee that major central banks will step in to purchase securities if yields rise too dramatically. This backstop fundamentally alters the risk calculus for private investors, who can reason.